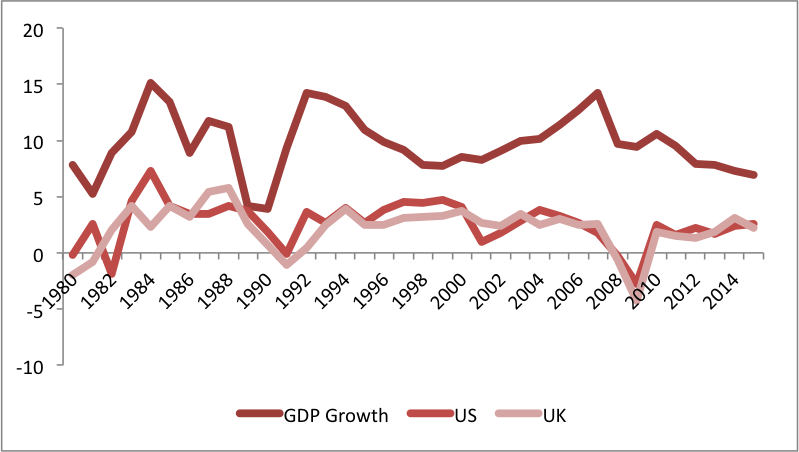

Economic Growth in China has slowed somewhat in recent times from the phenomenal growth experienced for much of the last 20 years. Most recently, in 2016, GDP growth of 6.7 per cent was recorded. It appears that China has now entered a new moderate phase of growth. This new era of growth has occurred as a result of a transition away from investment and export lead growth towards more sustainable growth that is anchored in services and consumer spending. This trend is set to continue with the latest forecasts from the IMF suggesting that China can expect GDP growth of 6.5 per cent in 2017 before expanding a further 6.0 per cent in 2017. This is in stark contrast to the average annual growth rate of 10 per cent since the 1980’s. Although the economy has clearly slowed down over the last few years , it is still among the highest in the world and far above some of the more advanced economies such as the UK and the US as shown in figure 1. It is interesting to note the particularly strong co-movement between the US and the UK which does not seem to be shared by China.

Figure 1

Source: World Bank

Source: World Bank

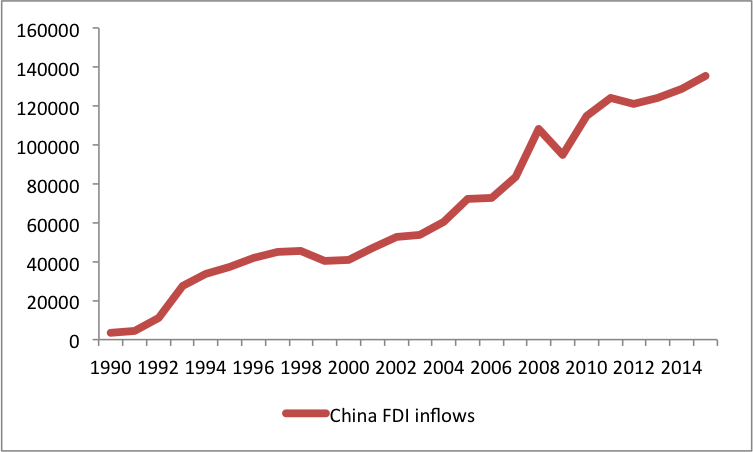

An interesting trend that has emerged from Chinese data over the last couple of years is the direction of capital flows. It appears that capital is quickly fleeing the country and making its way into foreign assets in places like the US, the UK and Europe. Upon entering the World Trade Organisation in 2001 there was a significant increase in exports and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into China which resulted in an increase in foreign exchange reserves at the central bank and an appreciating currency. This inflow of FDI was a major contributing factor to the large gains in productivity and double digit average economic growth that China experienced in the years that followed.

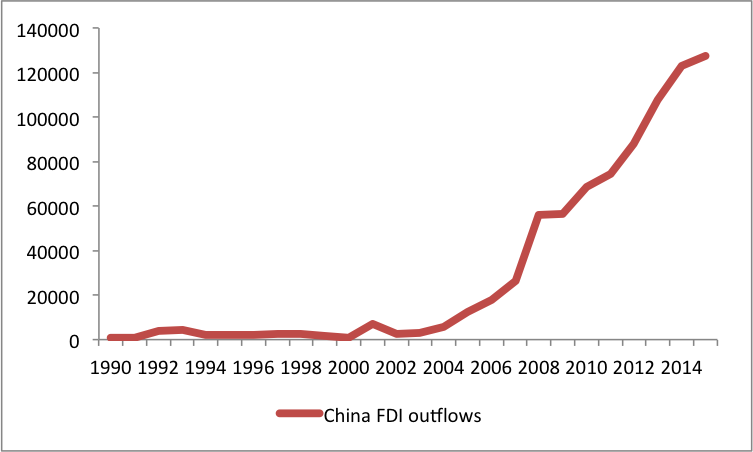

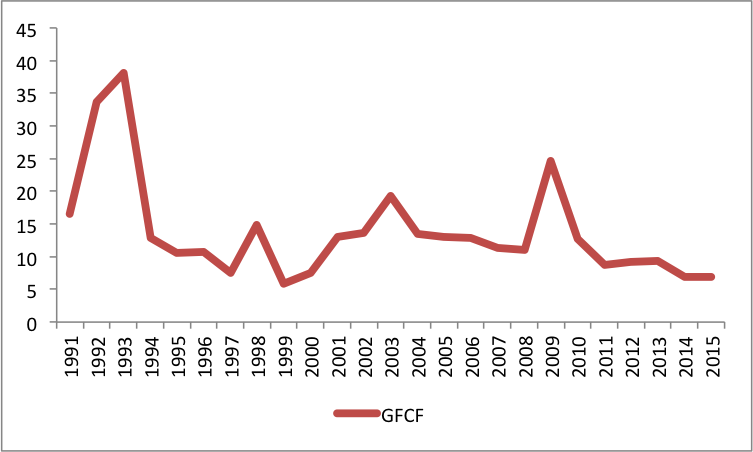

Figures 3 and 4 show the levels of inward and outward FDI in China up to 2015. The massive increase in capital moving in and out of the country is clear from the graphs. Perhaps the most interesting trend, though, is the surge in capital outflows. Since 2013, capital outflows have increased by 18 per cent and in 2016 alone is estimated to have been $200 billion, prompting increasing attention on the part of the government to try and cool the level of outward investment. At the same time, the level of investment (Gross Fixed Capital Formation) in the Chinese economy has fallen from previous highs in earlier years (Figure 4), contributing to the slowdown in productivity and GDP growth..

Figure 2

Notes: FDI inflows: Source United Nations

Notes: FDI inflows: Source United Nations

Figure 3

Notes: FDI outflows: Source: United Nations

Notes: FDI outflows: Source: United Nations

Figure 4

Notes: Gross Fixed Capital Formation: Source: World Bank

Notes: Gross Fixed Capital Formation: Source: World Bank

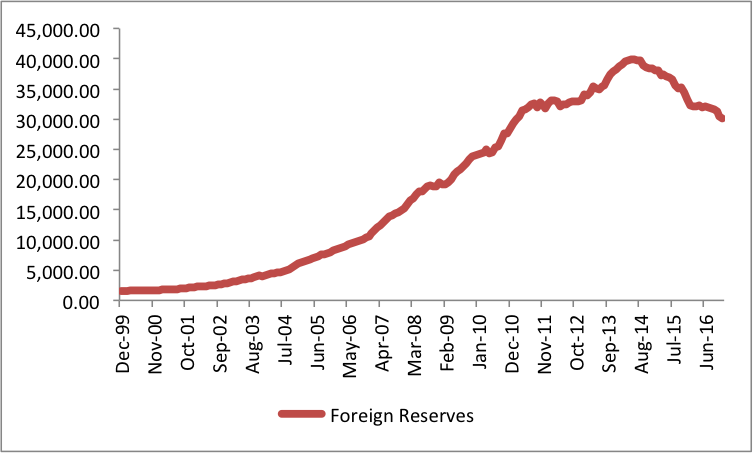

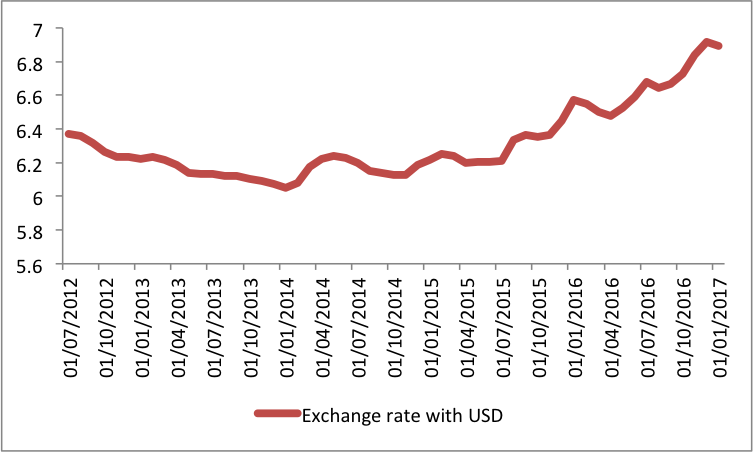

This large outflow of assets has led to dwindling supply of reserves of foreign assets as the PBOC try to stem the depreciation of the RMB. Figure 5 and 6 show exactly this.

Figure 5

Notes: PBOC foreign reserves

Notes: PBOC foreign reserves

Figure 6

Notes: Exchange Rate

Notes: Exchange Rate

We can see that reserves started to fall in mid 2014 and have continued to decline as the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) try and maintain upward pressure in a currency that is becoming increasingly less demanded in financial markets. Between May 2014 and November 2016 reserves fell by around 24 per cent. Although China has the biggest foreign exchange reserves in the world, they will eventually will run out and the currency will depreciate. A large part of the problem that China faces relates to what is known as the trilemma of international finance. Essentially, it states that a country can have any two of the following three: free capital mobility, a fixed exchange rate and independent monetary policy. To see why this is the case, consider the following example. Imagine the PBOC wants to lower interest rates while also keeping a fixed exchange rate. As the bank lower interest rates to support the economy during a period of slow growth or recession it will create downward pressure on the currency as investors move away from domestic assets in search of higher yields. If the bank also wanted free capital flows then the only way to keep the currency from depreciating is go to the open market and buy it with their stock of reserves. While the stock of reserves of foreign currency at the PBOC is rather large, it is certainly not limitless. Thus, they would eventually run out and the currency would depreciate. I hope this example makes it clear why a country can only have 2 of the 3 and not all simultaneously.

Now we know that this phenomenon is occurring. The question is why is it occurring? Well, one of the contributing factors at least is the slowdown in the rate of growth in China. 2016 was the slowest rate of growth observed in 26 years, contributing to a climate where high returns are becoming increasingly harder to achieve leading investors elsewhere in search of yields. Much of this slowdown, however, can be attributed to the government trying to reorientate it’s economy to a consumption and services based economy.

Another possible explanation is that as average incomes in China have risen significantly in recent years, after having invested heavily in real estate, household’s are now beginning to diversify their portfolios and reduce their exposure by buying into foreign assets which is contributing to significant outflows. The Bank of International Settlements suggest that the outflows may be as a result of Chinese firms paying down their dollar debt which could have accelerated prompted by the strengthening of the US dollar on the back of Trump’s economic policy announcements.

Risks to the Chinese Economy

More generally, there are a number of risks that threaten the future growth of the Chinese economy. I think it is worth talking about some of the challenges that China faces and will face in the future. The rate at which money is leaving the Chinese economy means that the level of investment is falling, contributing to the slowdown in GDP. This slowdown is part of the reason capital is leaving, creating a vicious cycle that could further threaten stability in the country.

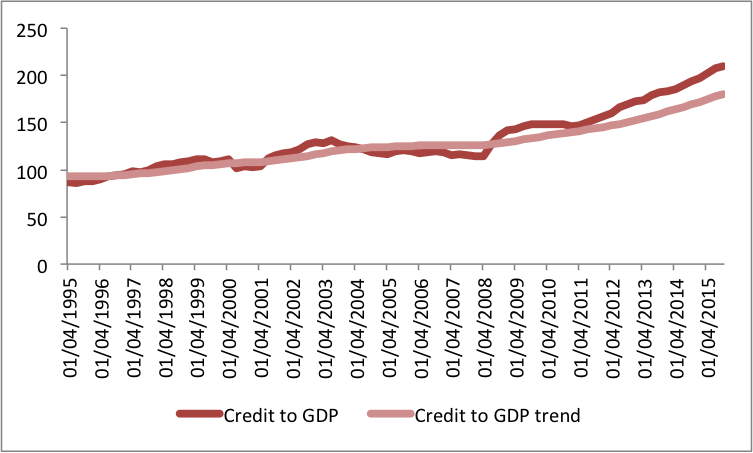

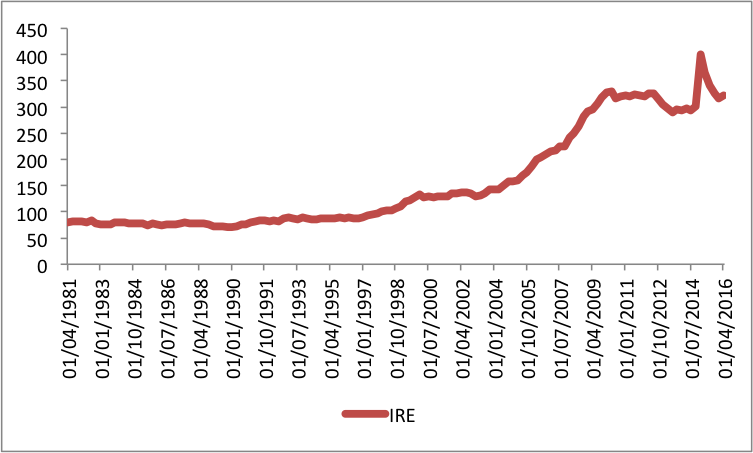

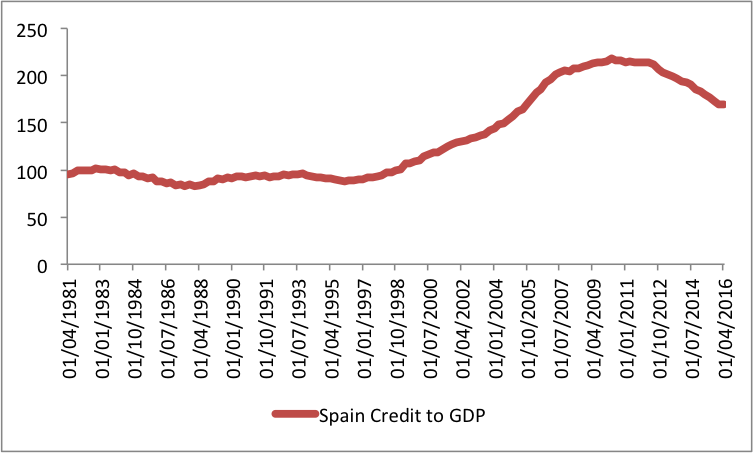

In an effort to keep GDP growth at a target of around 6 per cent, the government has been fuelling this, in part, by an increase in credit which is adding to an already huge mountain of debt. This level of debt is probably the single greatest risk to the Chinese economy. Figure 7 shows the ratio of credit to the non-financial sector to GDP versus its trend. We can see that while the series was relatively stable during the 1990’s and 2000’s, more recently a divergence has started to emerge. This kind of trend is not uncommon across countries prior to a financial crisis and recession. For example, the same divergence was clear in the case of Spain and Ireland who experienced pretty severe recessions as a result of excessive build ups of debt (Figures 8 and 9). This is not to suggest that a build up of debt will trigger a crisis, but it certainly makes the economy far less resilient if some other factor prompted a period of instability. Current data suggests that the debt is over two times the size of the countries GDP and doesn’t look like it will be falling anytime soon. The nature of the debt is such that is presents a very serious systemic risk to the financial sector and the wider economy.

Figure 7

Source: BIS

Source: BIS

Figure 8

Source: BIS

Source: BIS

Figure 9

Source: BIS

Source: BIS

The level of debt is not the only problem with the Chinese economy. There are other longer term demographic issues as well. The UN estimates that by 2050, a quarter of the Chinese population will be over the age of 65. which will have serious implications for the state in areas such as health and pensions. These problems are not unique to China and are in fact are serious problem facing many major economies including Europe and Japan which will have implications for potential growth.

What can China do?

There are a few things the government can do, however, to attempt to ameliorate some of these issues and some of these have been attempted already. The government has recently tightened capital rules by increasing regulation on outbound investment from state controlled firms. Latest data suggest that this may be working with a significant fall off in RMB outflows recorded in December. Whether this will be enough to permanently stem the flow is uncertain and they may have to be tightened further to avoid another record fall of the RMB against the dollar in 2017. The PBOC will also have their work cut out for them to undertake the appropriate monetary policy that carefully manages the stability of the financial sector while supporting the wider macroeconomy.

In terms of fiscal policy, the government are already undertaking fairly expansionary policies to try and boost consumption growth. They will likely need to continue to promote consumption in the medium term especially as long term demographic problems in China emerge. The reason China has an upcoming demographic problem is partly due the the longstanding one child policy. This has however, recently been eased, now allowing up to two children. According to the government, it has, so far, failed to have been as effective as expected and doesn’t look like it will be enough to offset the unfavourable demographics. One possible solution to at least alleviate some of the issues surrounding a declining labour force is to raise the retirement age. China has a fairly low retirement age compared to a lot of other countries so this gives them a little room to work with in the future.